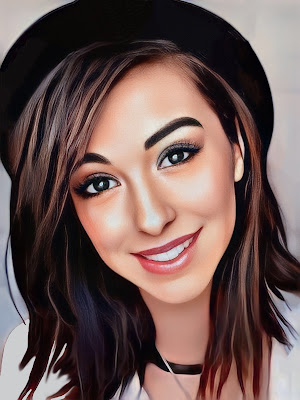

The simple facts are: Christina was a brilliant and creative musician and songwriter, a groundbreaking, innovative, and charismatic performing artist, and—above all—a great singer. But she also had the singular distinction of putting all of this into a “package” and communicating it through a new form of media when that interactive audiovisual media platform was still young and malleable, when its possibilities were still being discovered and invented.

YouTube was (and remains) the largest and most flexible “space” for the ongoing revolution that is flipping the whole dynamic of the relationship between the viewer and the screen—a dynamic that had dominated audiovisual media for half a century, which for my generation (the “late boomers” who never knew a world without ubiquitous TV) spanned our whole lives. It was like people hardly noticed the change as it was taking place. They started “watching” YouTube, and soon discovered that they could comment on the videos by opening their own YouTube account, and this account empowered them to post their own videos if they wanted to. Even if the vast majority of people remained “viewers” and didn’t “broadcast” their own videos to what rapidly became a global public audience, they could not avoid realizing that a new horizon had been opened.

In the first decade of the 21st century YouTube turned every viewer into a potential broadcaster. After 50 years of “watching TV,” it took me some time to realize that, suddenly, I had been invested with my own personal television station with the potential to reach anyone in the world… for free! Like most people, I didn’t have the skill or the time to make much use of it. But the younger generation adapted spontaneously and began to produce innovative content. YouTube—almost “accidentally,” without anyone realizing what was happening—connected creative people to the whole world in a way that was unprecedentedly simple and inexpensive. It was so easy to share videos on YouTube that kids could do it. So, they did.

Mostly, they did it for fun. Some also daydreamed wildly of being “discovered” by a rich and famous entertainment-industry-“gatekeeper,” taken under his or her patronage, and launched into superstardom. It was still a crazy dream 15 years ago, but it did seem slightly less impossible than before.

The daydream of being discovered—in itself—was an old and inextinguishable daydream in the minds of generations of youth. My band mates and I “dreamed” in the ‘70s of being “discovered” and becoming famous. Both myself and my fellow guitarist could take turns shredding epic leads (actually, we were pretty good). But none of us could sing. If only we’d had a “Christina Grimmie” at our high school! But it wasn’t meant to be, and in any case none of us were sufficiently driven by our daydreams in this regard. We were happy enough having a nerd-fest pouring over the latest music equipment catalogues and “dreaming” of owning a stack of Marshall amps and all the latest sound-altering gadgets.

After my own youth had passed, I continued to pay attention to the music scene, and I noticed the increased possibilities of sharing music through recorded media: quality cassette recording made “demo tapes” possible, and video tapes widened the sphere wherein one could seek an audience. Tapes could be copied and distributed through the mail. A simple demo tape might catch the attention of a person with bigger “connections” who might get it to a music manager who might pass it around until, maybe, an A&R developer at one of the many record labels in the vastly enlarged music industry took an interest in it. This could lead to a recording contract and, with determination and a lot of luck, eventual superstardom… which was the only way to spread your music around the world and build a global base of committed fans who appreciated and supported it.

Worldwide popular music success was necessarily linked to celebrity status, with all the vainglory, pressures, expectations, anxieties, isolation, and self-alienating and destructive behavior this status frequently entailed. Music needed new outlets, new ways expression that enabled the artist to remain in control of his or her craft.

Although I took up the teaching and academic profession and it remains the primary focus of my professional activities, I have also been immersed for most of my life in many facets of music. I have been on both sides of the stage in concerts of diverse genres. I was classically trained on the cello, and taught myself electric and acoustic guitar. I learned to read musical notation and wrote instrumental music (and I’m trying to revive those efforts). I have also participated in the tremendous expansion of media and technology for musical performance and recording that has taken place during the span of my own lifetime. From “stereophonic” vinyl records to cassettes to CDs to iPods to Spotify and streaming audio, from “concert films” and documentaries to multi-camera-angle television broadcasts to MTV to concert DVDs of outstanding quality, from basic musical instruments (which in themselves are the fruit of centuries of craft and technical refinement) to analogue electronic augmentation (I had a “transducer” in the 1970s to amplify my cello) and the complex, huge, and amazing versatility of the analogue Synthesizer (1960s-70s) to the increasing sophistication and digital transformation of the portable electronic keyboard… I could go on and on…

In any case, I knew that the outlets for musical creativity (and other forms of creativity) were bound to expand in the wild explosion of interconnectedness that the internet was spreading like fire in the global village. We were already seeing this phenomenon (with regard to the written word) in social media as the years passed in first decade of the 21st century. Blogs were everywhere. I began blogging in 2006, although my early ventures didn’t last. This present blog, however, has endured.

But I was blindsided by YouTube. When it first appeared, it seemed like just another way to watch videos. By the time my adolescent kids started showing me what was happening with YouTube creators, it had already been going on for some time and already had established artists. Only in retrospect did I see how it all began and how it grew.

Mainstream highly-produced music videos by pop stars grabbed most of the attention of music audiences and got the most “views” in the beginning—for that matter, they still do today. But people began to post their own videos, playing music and singing from their own bedrooms (and, sometimes, bathrooms—because of the superior acoustics there). This often began with the sense that only a small circle of friends would be watching them sing cover songs karaoke-style. But from the beginning, remarkably talented people stood out and drew larger audiences. At first, YouTubers were as surprised as everyone else to see their videos “take off,” to get encouragement and comments from people from distant places, and to accumulate more views than they ever imagined possible.

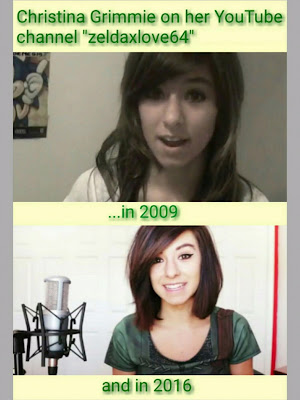

Among these creative pioneers was a 15-year-old girl from Marleton, New Jersey, named Christina Grimmie. In the Summer of 2009 she began recording cover songs in her room with a laptop and a webcam. What was rare about Christina from the start, however, was not only her singing quality but also the way she interpreted each song, arranging her own “stripped down” versions for piano and then accompanying herself live on her electronic keyboard. Even with relatively primitive recording equipment, Christina put enormous work into crafting performances that were perfect (or nearly perfect) from start to finish. Her agile, beautiful voice and her unique arrangements captivated people in those first days. I try to imagine how astonishing it must have been to go through a bunch of different videos and suddenly stumble upon this girl expertly playing her piano and singing like an angel songs that you had heard “on the radio” (or wherever) before but that you had never heard in the form Christina Grimmie had given them. She brought her own sense of beauty to the songs she played and sang in that room, in front of a poster of Sonic the Hedgehog.

She was a regular kid—with no promotion, no overhead, no tricks—creating beautiful new renditions of popular songs and broadcasting her videos directly on to your screen. I can only imagine what it must have been like to see her in those days, when the videos that (thankfully) we can still watch in her archives were posted fresh—for the first time—entirely unique in comparison to any of the other content surrounding them. It must have been a cause for wonder. It certainly inspired other young artists who came after her to take the risk of sharing their best music, to take the new media platform seriously, to “aim high” in their artistry.

Of course, it wasn’t long before Christina was noticed by people who could help her advance her music career in more conventional ways. She gained everyone’s attention in those few unforgettable weeks in 2014, on Season Six of The Voice (broadcast in the USA on “old-fashioned” network TV). Her singing became more expansive and more passionate as she gained experience and her voice began to mature, and as she expanded the repertoire of her own original songs. During those final two years, her music became more inspiring, comforting, thrilling, evocative, luminous, and soul-shaking. Still she stayed with her YouTube channel and continued her series of inimitable cover songs. She had frands all over the world, and met some of them face-to-face in tours and performances in Europe, Singapore, the Philippines, and the USA. Her voice and her talent were at the level of once-in-a-generation by the time she was 22 years old. I tremble when I imagine how great she might have become. For anyone who is an artist, or a human being, the awful tragedy of Christina Grimmie’s death seven years and one month ago is an enduring sorrow. We will not see or hear the likes of her again in these times (even if we are sustained by the hope to be with her again in God’s kingdom, where all sorrows will be turned to joy).

Still, she left a creative legacy that remains foundational for music and media in our time, and—undoubtedly—for the times to come.