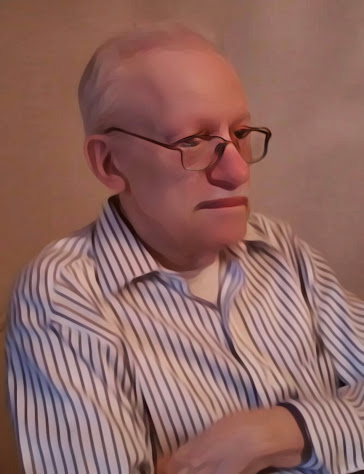

I am more and more grateful for my Dad. As I grow older, I feel like I “understand” him better, in part because I see how I am in many ways resembling him more and more—the “apple [really] doesn’t fall far from the tree”—and I see more clearly how his quiet attention was full of love for us—love that became more “gratuitous” over the years.

I am not “quiet and simple” the way he was, but I understand more how he saw his family and all of life as a gift. His love, always consistent, was his response and his gratitude for this gift—which he didn’t need to understand completely or to dominate in order to receive it and engage himself in the effort, responsibility, and creativity it required.

The gift of life, his family, and his work drew him all through his years, embodying and signifying the embrace of Love that was always present as his sustenance and his destiny—greater than the terrible wounds of the deaths of his own parents when he was a child, greater than the mistakes and failures and limitations that came every day, full of forgiveness and renewal, embodied and signified, too, in our own poor love for him and our “suffering with him” (at his bedside and in our own hearts) in his final days.

Dad is still teaching me to grow in patience and peace of heart, and gentle, consistent fidelity to the gift of everything (even now, while I continue to be noisy and ambitious and anxious—although *less* so as time passes). The Gift is greater, remains with us, carries us through our failures and incomprehension and even our betrayals.

As I become older and remember my Dad’s affection and tenderness toward us and his grandchildren in his older years, it strikes me that older people often live with a greater and deeper attention than we give them credit for in our youth. They look upon us with a kind of serenity that is akin to wonder, recognizing all the goodness in our being and growing, more easily forgiving our inattentiveness and superficiality because they’ve seen so much of that through the years; it doesn’t surprise them or disappoint then much anymore, but what does surprise them is the tenacity of the goodness of reality, the promise of fulfillment that endures in all the persons and all the positiveness of reality that are given to them in the present moment.

I think older people look upon us with immense gratitude and compassion, even when they seem to be grumpy—and Dad was never grumpy before his mind failed, and even after that it was more confusion and frustration than grumpiness. I’ll always remember how he would see Josefina and burst into a huge smile (even after he had forgotten her name). That smile, ultimately, was meant for all of us.

So many elderly people are lonely and they suffer greatly from it. But they have so much to give, and we who neglect them are perhaps the ones who are more impoverished. We hold back from their love because we are “too busy” or too distracted or too afraid. We are preoccupied with desperately trying to manufacture an artificial, broken, distorted, cheap imitation of the happiness that is offered to us every day as a gift. We ignore the gift, or we don’t trust it. We think our happiness depends on our own plan, our own ideas, our own power. But we don’t know what we want.

The elderly have passed through all of this, and now their plans are few and they have lost their power (some even lose their “ideas” or ability to think). They are tempted to bitterness and discouragement. But they can also be surprised to encounter anew the beauty and goodness and promise of the gift of life, the gift of being human, that has never abandoned them, that is still offered to them, and the Giver who is the depths of all gifts; indeed, the Giver who has *become the gift* and shares their powerlessness in the Love that “wants to” stay with them, always: the Love we all desire, the Love that alone can give us peace.

Thank you Dad, for everything. May the Lord fulfill you in His eternal embrace, where—I hope and pray—we will all be together again in the end, with every tear wiped away, forever.