This has struck me in a personal way. Everyone from my generation knows "the Queen" (no further specification was necessary). English speaking peoples in particular - regardless of whether or not they were her "subjects" - were aware of her as a kind of cultural institution. I remember her from my childhood. There are very few established public figures from my childhood that are still alive today. But the Queen and her royal family have lived very much "on the stage" of the latter half of the 20th century and the 21st century thus far. She was a consistent presence in everything from global politics to gossip. She was "around" and "in the background," like a mountain. As the years went by, she didn't seem to change very much. So many things were changing, wildly changing, in my younger days, but the Queen remained statuesque, a living "monarch" who was pictured on Canadian money and associated with so many English traditions that were familiar to all of us. We knew that she didn't have any "real power" and yet somehow she "mattered" in the U.K., and that sense echoed throughout the English-speaking world.

The "British Invasion" of popular culture in North America was (and remains) a formative influence for anyone who listened to music or watched television in my lifetime. I have never considered myself an "Anglophile" - I have no ethnic connection with the British, and their stiff-upper-lip ways are decidedly different from my own. But the English language does create a certain kind of common bond. The waves of British cultural influence have affected that bond during my life. It wasn't only the Beatles and all the subsequent music; it was also Shakespeare on television, and the quality of British actors in various dramas and comedies that were an inseparable part of the Anglo-American experience (from Brideshead Revisited to Fawlty Towers). And Her Majesty the Queen was always on the horizon.

In 1981, I watched the wedding of Prince Charles to "Lady Diana Spencer" on television, because back then there weren’t so many live broadcasts of internationally significant events, much less something as colorful and unusual as a royal wedding. I knew some things about Prince Charles too. I knew that "someday" he would be King, though I expected it to happen much sooner than 41 years into the future. (I also knew that Charles played the cello, which interested me because I also played the cello. Little details about the royals - not anything shocking, in those days - were always popping up in magazines and such.) Charles was "preparing" to be King in the 1970s, then in the 1980s, and then everything fell apart with Princess Diana and it began to appear that it would be better for Charles live out his life quietly in some corner and never become King. Into the 21st century, Prince William entered the scene with Kate Middleton, and Williams’s father seemed more or less on the shelf, a retired heir, while the Queen looked like she would just go on forever. Now, suddenly, in 2022, she is gone from this world, and he is King Charles III.

May God grant eternal rest to Queen Elizabeth II. Now, for the first time in my lifetime, the British are once again singing, “God Save the King.” In the whirlwind of fresh turmoil that seems inevitable to me in the near future, the King is not the only one who will have to grapple with new and difficult challenges. The English, for the moment, are holding back their worries over the future of their monarchy, but in the long run it’s hard to envision how that future might unfold.

I can’t say it’s the highest on the list of my worries. After all, my country declared independence from the British monarchy 246 years ago. Part of what shapes the imagination of people in the United States of America is that we don’t have any kings or queens here. Right? As a native citizen of the U.S.A., I’m expected to view any form of monarchy as antiquated at best and tyrannical at worst. But I have studied too much history to dismiss the potential for monarchy - in certain nations - to be a constructive, organic element among interrelated political institutions that serve the common good of persons in society. For example, many democratic countries today have some kind of more-or-less symbolic "Head of State," who is not involved in the political or legislative process, but who serves as a "ceremonial" leader: someone who presides over national celebrations, bestows honors, receives diplomats, and represents "national unity" from a perspective "above" the often-contentious political fray.

This public figure is often an "elder statesman" of some wisdom and good judgment who does not have effective political power to initiate government action, or to make, veto, or enforce laws, but who does have some measure of "soft power" as master of ceremonies, ambassador-at-large, mediator, advisor, and point of reference for continuity in the midst of changes in the actual government. He or she may exercise a formal constitutional role in appointing ministers and approving legislation, but the constitution itself prevents him or her from changing decisions of the democratically elected legislature.

This office is effectively the equivalent of a "constitutional monarch," and in a Republic is often styled as "President" (e.g., the "President of Italy" is one example that comes to my mind). Government institutions vary in particulars from one nation to another, but this type of ceremonial/symbolic presidency is particularly suited to nations that are structured according to the "Westminster Model" of parliamentary democracy (which is, of course, the British model in its broad elements), in which the leader of the majority political party - or governing coalition - in Parliament is the de facto head of government, with the title of "Prime Minister." In such a system, the quasi-monarchical "President" is elected directly or indirectly for a long - though usually not unlimited - term of office. Such Presidents serve as the custodians of the dignity of public life in their countries, and in relation to other countries.

It is not difficult for new nations to design an office of this kind, and provide for a ceremonial Head of State who serves a definite term in this “presidential office” practicing the valuable art of “political diplomacy” as his or her contribution to building up the common good. But the particular type of hereditary monarchy that acquired its distinctive style in medieval Europe is by its very nature an institution with centuries of heritage, and if it exists in any form today in some European countries it is because it has retained consistent popular approbation.

Generally, kings and queens in a constitutional monarchy fulfill many of the roles of "Presidents" described above. The hereditary feature, however, allows a royal family to also serve as a vital link to the past, the achievements of previous epochs, and the historic and natural beauty of the land itself where the citizens dwell.

It’s hard to imagine how a new nation could set up a useful hereditary monarchy “from scratch” in the world today. The rituals, customs, and popular deference that give such monarchies the supportive context for carrying out their national roles are not things that can be manufactured. They must emerge from many generations of history, and they endure by balancing consistency with flexibility that allows them to adapt in the face of historic changes. But if a country already has an ancient monarchy that has adapted itself to remain vital within the participatory and representative democracies of our time, I think they would lose an important component of their national life and cultural patrimony by simply getting rid of it.

The British monarchy has had its ups and downs over the course of more than a millennium, to say the least. Its greatest tragedy remains its role five centuries ago in the violent separation of Anglican Christianity from the Catholic Church shepherded by Christ through the Successor of Saint Peter. Ironically, while distancing itself from Christ's sacramental presence in the Catholic Church, the British monarchy preserved (but also to some extent “petrified”) many of the outward forms of monarchical ritual, solemnity, and pageantry from the Middle Ages. It is hard to see much real value in these unique features of the British monarchy except insofar as they remain echoes of the Catholic people who once recognized their significance. Today, of course, the U.K. is a society of many ethnicities and diverse religions. It is also a troubled and divided society. At the same time, the Catholic Church has been undergoing a small but persistent renewal ever since the conversion of the great Saint John Henry Newman in the mid-19th century. We must continue to hope that the monarchy will set itself aright once again, at least regarding its claim to “rule over” (even symbolically) the Anglican communion as England’s official, “national form” of Christianity. A secularized Britian with a monarchy entering into a period of lower profile may create conditions in which this long and necessary process of healing and reconciliation can flourish and grow in new ways. May Jesus and His Holy Mother grant that it be so.

The British monarchy has had its ups and downs over the course of more than a millennium, to say the least. Its greatest tragedy remains its role five centuries ago in the violent separation of Anglican Christianity from the Catholic Church shepherded by Christ through the Successor of Saint Peter. Ironically, while distancing itself from Christ's sacramental presence in the Catholic Church, the British monarchy preserved (but also to some extent “petrified”) many of the outward forms of monarchical ritual, solemnity, and pageantry from the Middle Ages. It is hard to see much real value in these unique features of the British monarchy except insofar as they remain echoes of the Catholic people who once recognized their significance. Today, of course, the U.K. is a society of many ethnicities and diverse religions. It is also a troubled and divided society. At the same time, the Catholic Church has been undergoing a small but persistent renewal ever since the conversion of the great Saint John Henry Newman in the mid-19th century. We must continue to hope that the monarchy will set itself aright once again, at least regarding its claim to “rule over” (even symbolically) the Anglican communion as England’s official, “national form” of Christianity. A secularized Britian with a monarchy entering into a period of lower profile may create conditions in which this long and necessary process of healing and reconciliation can flourish and grow in new ways. May Jesus and His Holy Mother grant that it be so.

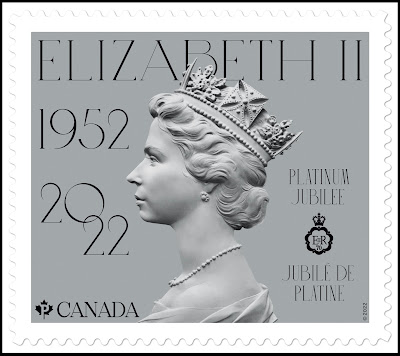

Queen Elizabeth II was probably “existentially ignorant” of the real meaning of the destructive rupture that took place when her predecessors imposed (sometimes brutally) upon their realms and peoples a separation from the fullness of Catholic unity in the 16th century. She was also hindered by other limitations of perspective, and yet she accomplished much that was admirable in her long reign. The fact that the British monarchy has survived to 2022 (and has a chance at continuing to be valuable in the future) owes much to the long years of dignity, persistence, and dedication that Queen Elizabeth brought to her seven decades of service in the midst of so many changes and so much immense material growth as well as dizzying upheaval.

The two pictures below give us a sense of how remarkable and how historically extensive the quiet work of the Queen was during her 70-year reign. As Queen, Elizabeth II was served by no less than 15 Prime Ministers. In the picture on the right, we have the last public photograph of the Queen, who formally received the newest British Prime Minister Liz Truss on September 6 at Balmoral Castle (two days before her death). In the picture on the left, young Queen Elizabeth greets her first Prime Minister in 1952. His name was Winston Churchill.

The two pictures below give us a sense of how remarkable and how historically extensive the quiet work of the Queen was during her 70-year reign. As Queen, Elizabeth II was served by no less than 15 Prime Ministers. In the picture on the right, we have the last public photograph of the Queen, who formally received the newest British Prime Minister Liz Truss on September 6 at Balmoral Castle (two days before her death). In the picture on the left, young Queen Elizabeth greets her first Prime Minister in 1952. His name was Winston Churchill.